Home > Cricket > World Cup 2003 > Columns > Prem Panicker

Team building, brick by brick

March 02, 2003

SO India is in the Super Sixes; with 8 points that give it a head start in the race for a semifinal berth.

In getting there, they have come a long way from the shambles of New Zealand. The journey has underlined, maybe even exaggerated, their strengths and weaknesses, their sublime beauties and near-fatal flaws.

They started with an indifferent performance against Holland, and followed it up with a pathetic outing against defending champions Australia.

Back home, a land that makes a religion out of cricket turned seriously apostate; images of the gods were burnt, effigies fired.

The sparks from that unrest crossed the continents and ignited the team, brought it together in the now famous huddle suggested to them by sports psychologist Sandy Gordon.

The sparks from that unrest crossed the continents and ignited the team, brought it together in the now famous huddle suggested to them by sports psychologist Sandy Gordon.

"We are not getting support from outside," said skipper Sourav Ganguly. "So we have to seek it among ourselves."

The batting fired, the bowlers smoked. Four wins, each more emphatic than the other, followed.

The Indian cricket team is like that - pure, unadulterated theater. The lights dim, the curtain goes up and you tense in anticipation, you prepare to suspend disbelief.

You can never be quite sure what you will get, and whether the latest offering will merit a standing ovation or stinky-rotten tomatoes. But you do know that high drama is inevitable; that the team will stun you with either ineptitude or blinding brilliance.

So, now what?

COUNT, on the credit side of the ledger, Sachin Tendulkar Mark II. Or is it III?

Since my colleague Krishna Prasad is writing a column on his performance in this World Cup, I will only take up as much space as it takes to say that when commentators of all hues call this the greatest one day innings of all time, or when Tendulkar himself ranks this innings above that one ('It is the World Cup, and it is against Pakistan'), I disagree. (Okay, so this is just my opinion.)

Since my colleague Krishna Prasad is writing a column on his performance in this World Cup, I will only take up as much space as it takes to say that when commentators of all hues call this the greatest one day innings of all time, or when Tendulkar himself ranks this innings above that one ('It is the World Cup, and it is against Pakistan'), I disagree. (Okay, so this is just my opinion.)

I don't know about all time, or even recent vintage - who in heck has seen them all?

It is not even, for me, the best Sachin has played - that honor goes to the April 22, 1998 innings of 143 versus Australia in the midst of a dust-storm in Sharjah (next highest score, 35).

Having said which, this knock has to rank way up there in the gallery of modern masterpieces. The thing with batsmen of this caliber is that long after they have done painting an exquisite canvas of aggression, individual brush-strokes keep coming back to excite the memory.

...Like the back foot extra cover drive off Wasim Akram that started the carnage.

...Like the defensive push - or so we thought - in Akthar's first over, that raced to the fence; a Tendulkar shot like no other, speed of eye and speed of hands producing a moment of instant magic

...Like the whip to square leg to a Younis delivery outside off and going further away; the kind of angle only a cricketing Pythagoras can conceive, and rubber-band wrists execute.

There were many such shots, stunning swathes on a canvas painted in glowing earth tones.

There was also, in this innings as in fact throughout this tournament, the signs of a cricketing mind at work. In recent times, Tendulkar has tended to get out in one of two ways - either the upper edge into the slips-gully region seeking to force square, or the bowled/LBW through the gate as he looks to come forward to the delivery just outside off seaming/swinging in.

It took him one adjustment to counter both - thus, in each innings thus far, he has tended to shuffle across his stumps even to the really fast bowlers, shut the bat face (no more edges), straighten the back lift and follow through (no more "gate") and work off, or even outside off, to leg at angles so acute they defy Euclid.

The likes of Geoffrey Boycott have made a career out of eradicating error - but to achieve that without diluting aggressive intent takes some doing.

Thus far, this World Cup has seen a compleat Tendulkar: Dedication to a cause  , focus

, focus  , concentration

, concentration  , resolution

, resolution  , sublime skills

, sublime skills  .

.

Too often over the last two or three years, a Tendulkar innings has been like good sex - you want it to last forever, but it never does. In this World Cup, finally, longevity is being allied with lustrous shot-making, and that arouses anticipation for the rounds to follow.

Apres Sachin, la deluge - wasn't that how it went?

Tendulkar made his Test debut on November 15, 1989 and his one day debut on December 18, 1989. Since then, he has made 8,811 Test runs (31 centuries) at 57.59, and 12,000-something ODI runs (average 44.5, 34 hundreds, a strike rate of 86.6 per cent).

What's the use, is a commonly asked question: that mountain of runs, what exactly has it won for us?

Very little, admittedly - so where lies the importance of Tendulkar?

Perhaps because he hasn't aged, perhaps because he has become such a peripatetic part of our lives that we don't think in terms of years, it never occurs to us to think that this bloke has now been around for 14 years - and incredibly, no one is even thinking to when he will retire.

Krish Srikkanth, Navjot Sidhu, Mohd Azharuddin, Ravi Shastri, Kapil Dev, Sanjay Manjrekar - the commentators of today were his peers when he started out.

Tendulkar has seen an entire generation of Indian cricketers go; he has seen the next generation, comprising the Rahul Dravids and Javagal Srinaths and Anil Kumbles and Sourav Gangulys, come and establish themselves and even reach the age where they begin to think of quitting; he is now seeing yet another generation enter the ranks.

It has been a fallow period for Indian cricket, with wins at home hardly masking the sequence of defeats abroad. And through this darkness, Tendulkar has kept the light of quality batsmanship burning in the window - a light that, today, is inspiring the likes of Yuvraj and Kaif and his own doppelganger Sehwag.

That lonely vigil, though, seems to be nearing its end. GenNext is here, they've seen the light, and are now seemingly ready to take it forward. It is a new, brash generation - one that is not ready to buy into the "Sachin out, all out" mindset, one that has grit and nerve and determination and an absolute unwillingness to burden themselves with the baggage of losers.

We saw the first glimpses of this new generation in England, during the NatWest Trophy, last year. More glimpses in Sri Lanka, during the Champions' Trophy. And here, on the biggest stage of them all, we see the tykes gradually find their feet, shed their nerves, and claim their places on the stage.

ENTER, left, Mohammad Kaif.

'Isn't he coasting on his past laurels?', someone asked us in Panix Station a while back. Others, back home, asked the question with black tar.

'Isn't he coasting on his past laurels?', someone asked us in Panix Station a while back. Others, back home, asked the question with black tar.

The first part of his answer came in the match against Zimbabwe, in course of a crisp little cameo that produced a moment of brilliant improvisation. He walked across his stumps from leg to off, somehow managing to go forward at the same time that he went sideways, converted a perfectly good delivery on line of off stump into a full toss, and flicked it over the backward square leg boundary for six.

He fielded out of his skin throughout, even when batting form deserted him - but his work against England was a moment to cherish. Nick Knight is adjudged one of the better runners, his run out is now being termed the mistake that cost England the game.

That takes away credit from where it is due - Knight pushed to mid on, Kaif was at cover, the ball was to his wrong side and yet, he covered the turf in a trice, picked up wrong-handed on the forward dive, threw the ball at the single stump in continuation of the dive, and caught the surprised batsman a good five yards short.

And finally, he came in yesterday against Pakistan at the unaccustomed number four position, and at a crucial moment in the game with his side two down in two deliveries. I must confess, given the prevailing climate, to a moment of apprehension - what if pressure gets to him? What if he, a Muslim, fails against Pakistan? It does not take much imagination to figure what would have been said.

I needn't have bothered - Kaif produced an innings of temperament, maturity and class, batting in a fashion that allowed Tendulkar to relax and go about his business unworried by the prospect of a procession at the other end. And he put the seal on that performance with a shot that, even against the background of the Tendulkar master-class, was special: Younis produced a reverse-swinging yorker, the famed toe-crusher albeit at less pace than in his pomp. Kaif, with a little shimmy, made room and seemed to push the ball away from him - no one moved, as the ball sped bullet-like to the straight boundary.

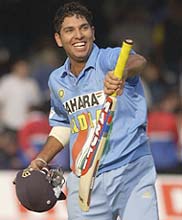

ENTER, center, Yuvraj Singh.

Shortly after he debuted in dream fashion in Nairobi, Faisal Shariff met him for an interview. The youngster strolled in an hour behind time and, first crack out of the box, drawled, 'You know, I am the Hritik Roshan of Indian cricket, too many people want time with me these days.'

Shortly after he debuted in dream fashion in Nairobi, Faisal Shariff met him for an interview. The youngster strolled in an hour behind time and, first crack out of the box, drawled, 'You know, I am the Hritik Roshan of Indian cricket, too many people want time with me these days.'

Success - too much, too young -- is a heady drug, and it has destructive potential. Ask Sadanand Vishwanath, in my book the best modern wicket-keeper India has produced; ask Laxman Sivaramakrishnan, the man who made spin fashionable in ODIs long before Shane Warne's name made it into an international scorecard; ask Maninder Singh the heir presumptive of Bishen Singh Bedi.

When Yuvraj's batting went to pieces shortly thereafter, and he found himself out of the side, one feared that his name would be the latest addition to that list. Had he been an Australian, it would have been okay - the Aussies know how to guide, nurture, conserve and preserve young but truant talent (ask Damien Martyn, Ricky Ponting, even Mathew Hayden). In India, there is no support system for a young man in that situation.

Yuvraj lost his way, then found himself again and returned with focus and strength of character adding a patina to his talent. His 42 in 38 deliveries against England was hors d'oeuvres of the most appetizing sort - coming in with the innings becalmed, he lent it urgency with electric running and inch-perfect strokes, hauling the team by the scruff of its neck to a challenging total.

And then, yesterday, he didn't simply absorb the pressure of coming in after Tendulkar against a pumped up Shoaib Akthar - he turned it back on the opposition with an innings of composure and classic stroke-play, in which the cover and off drives rivaled those played by Ganguly in his prime for grace and ease of execution.

Two young talents slotted themselves into the team matrix, slotting themselves alongside the rock-solid Rahul Dravid, whose wicket-keeping appears to have given his batting a fillip (average as batsman, 35-something; average as keeper-batsman, 47+).

Apres Sachin, la deluge? Not any more.

The team is a batsman, maybe two, short of a full deck still - but the nucleus is increasingly visible, and it is no longer about one man. And when was the last time we could say that?

WITH India, it has always been a case of what the batsmen make, the bowlers give away – or vice versa. It was either a good batting attack burdened by a bowling lineup that was either too brown or too green; or bowlers doing a great job only for the batsmen to prove incapable of building on it.

Harbhajan Singh's entry into the ranks was a start – young, aggressive, a competitor with the ball, a maddening improviser with the bat, and a safe fielder in most positions.

Zaheer Khan came long and, like Yuvraj Singh, lost his way for a while in a miasma of laziness and uncaring before getting his act together and transforming himself into the attacking, in-your-face seam spearhead.

Javagal Srinath has, for long now, gone about his work like a man carrying the burden of a dozen – and a look at the bowling support he has had (or more accurately, not had) at the other end is enough to explain that demeanor.

Lately, it is as if he took a swig at the elixir of youth (I wonder if that kind of thing shows up in a drug test?). And he has responded very well, bowling at the peak of his powers and, more importantly, taking up the leader's role, giving his younger mates the kind of help and encouragement he himself never got during his initial days, spending time with them and pushing them to learn, and excel.

And finally, there is Ashish Nehra, the lad with the lanky limbs and goofy grin of vacuous good humor; the perennial spare wheel in the Indian seam attack.

His action was a guaranteed groin-buster: Try bowling with your leading foot pointing down the track and your rear foot pointing to the sightscreen at your back, you'll see what I mean.

His ankle was dodgy – a year ago, he had to go to England for surgery to remove a growth (an incident that escaped universal notice and bold-type headlines because who in heck noticed Ashish Nehra anyway?).

Quietly, away from the limelight, he worked – on fitness and strength with Adrian le Roux, on his bowling with assorted coaches, with help from senior mates Srinath and Zaheer and telephone calls and encouragement from his mentor, Wasim Akram.

He made them all sit up with a 149.1k delivery in the game against Zimbabwe; added an element of drama by falling into the delivery stride of the second ball of his first over in the next game; kept a nation on tenterhooks and physiotherapist Andrew Leipus on active duty for the next three days, then came back to the ranks and bowled out of his skin to win India a very crucial game against England.

2/74 against Pakistan might make the 6/23 of the earlier game seem a flash in the pan – but put that 2/74 in context of a flat batting track and the figures of 1/72 for Akthar and 2/71 from 8.4 overs in 8.4 overs for the near legendary Waqar Younis; add the seasoning of a spectacular reverse-swinging yorker to get rid of Saeed Anwar before he could move up the gears after getting to his hundred.

It's not quite the finished product yet – but finally, India appears to have the makings of an “attack”.

“Not the finished product”, in fact, applies to the team in its entirety: Dinesh Mongia has shown nerve and courage, but not – yet – the confidence to translate batting time into big runs; skipper Ganguly hinted at batting rehabilitation with a hundred against Namibia but has lapsed into his old ways leaving the side, effectively, a batting short; Anil Kumble's outing yesterday did little to suggest form; “bench strength” is a misnomer for the “all rounders” Agarkar and Bangar; Parthiv Patel will return from the Cup a much better drinks provider and odd job man than wicket-keeper…

And yet, it is a start on the road to team building. On the plus side, India goes into the next stage with less real pressure than it faced in the prelims – and that means it has the time to apply course correction where required.

By way of tailpiece, a statistical quirk my colleague Krishna Prasad pointed out: In 1983, India won the Cup. In 1987, India was a semi-finalist. In 1992, India was eliminated. In 1996, it was a semi-finalist. In 2000, it was eliminated.

No comment; any extrapolation is entirely your own.

More Columns